A brief historical overview of cinema in Tibet: Earliest references

In old Hollywood films of intrepid white explorers encountering savages in darkest Africa (or tribals in benighted Afghanistan) there is usually a decisive moment in the story when the bwanas (or sahibs) are captured and it appears they are done for. The situation is resolved by the explorers demonstrating white-man magic like predicting a convenient solar eclipse (King Solomon’s Mines) and overawing the natives. Less dramatically but with similar results the sahib might crank up an old Victrola and “soothe savage breasts” with the voice of the great Caruso. Then of course there is the scenario where a film projector is used to illuminate the side of a temple or a cliff face with moving images that terrifies the natives into submission.

It is nice to note that this Hollywood cliché was stood on its head when the first (invited) British mission reached Lhasa in 1920. Charles Bell, the head of the mission, tells us that the commander-in-chief of the Tibetan army (Tsarong Dasang Dadul) entertained him and his party with some film shows in his private screening room. Bell notes that Tsarong operated the projector himself quite competently. Bell was probably not expecting to watch a movie in “Forbidden” Tibet, and it is to his credit that he tells us the story. Travellers to Tibet — even now in the 2000s — tend to play up everything that is strange and esoteric, and gloss over any indication of modern amenities that might perhaps detract from the hardship aspects of their accounts.

It is nice to note that this Hollywood cliché was stood on its head when the first (invited) British mission reached Lhasa in 1920. Charles Bell, the head of the mission, tells us that the commander-in-chief of the Tibetan army (Tsarong Dasang Dadul) entertained him and his party with some film shows in his private screening room. Bell notes that Tsarong operated the projector himself quite competently. Bell was probably not expecting to watch a movie in “Forbidden” Tibet, and it is to his credit that he tells us the story. Travellers to Tibet — even now in the 2000s — tend to play up everything that is strange and esoteric, and gloss over any indication of modern amenities that might perhaps detract from the hardship aspects of their accounts.

Of course, the cinema was a novelty in Tibet in 1920 and probably Tsarong’s was the only projector in Lhasa, though the Dalai Lama would most probably have owned one. For all other Tibetans the closest thing to the movies, or at least to a show that used lights and special effects, was the Sang-Thag theatre of the Lower Tantric college (Gyumey) in Lhasa. I saw a show in 1971 or thereabouts in Dharamshala, in the post New Year Monlam festival. As the name “secret string” indicates it was a puppet show. It was not limited to string puppets but utilised a variety of techniques for its effects. The Sang-Thag was not a show in the sense of entertainment but actually an offering (choepa) part of “Offering of the Fifteenth” (Choenga Choepa), the main feature of which were the amazing butter sculptures crafted by the Upper Tantric College (Gyutoe). In spite of its votive purpose the puppet show was nonetheless hugely entertaining.

The puppets performed in a small proscenium stage lit by an electric bulb. In old Tibet it would have been butter lamps, but electric lights might have been used after 1927 when the first hydroelectric plant was built in Lhasa. The Sang-Thag theater did not have a plot or a story line but consisted of a series of beautifully staged tableaux. A tiny monk appeared on the roof of monastery and beat a gong to wake up the monastery. A congregation of monks filed into the assembly hall. This was done with a row of figures on hidden springs, all rocking back and forth in a convincing manner. An oracle went into a trance and beat his secretary with a stick – and so on. At the end of the show the curtains were closed and children cried out “cheonga choepa lao sangthag chik thenrok nang” or “O “offering of the Fifteenth”, please pull a secret string” till another show started.

The earliest reference we have to an optical entertainment device in Tibet is from around 1775. George Bogle, the envoy of the East India Company sent to Tibet by Warren Hastings, mentions that among the curiosities belonging the 3rd Panchen Lama was “… most surprisingly of all, a camera obscura or peep-show with scenes of London.” The sage Jigme Lingpa in his Discourses on India written in 1789, discusses the British, the Ottoman and the Moghul empires, and specifically describes England and its various manufactured exports: telescopes and modern weapons etc.. He describes in some detail contemporary novelties as a barrel-organ. But then he also mentions that “On top of this box “within a raised glass door the foreign countries are revealed, the images of these countries being laid down and made clear upon a mirror inside, and so by magical means the details of the great countries are beautifully drawn; and the design of the countries of the world which are executed upon various little panels appear enormous inside the glass door.” I am not certain if Jigme Lingpa was describing a zograscope, a peep-show or an optical viewing box of another kind.

The earliest reference we have to an optical entertainment device in Tibet is from around 1775. George Bogle, the envoy of the East India Company sent to Tibet by Warren Hastings, mentions that among the curiosities belonging the 3rd Panchen Lama was “… most surprisingly of all, a camera obscura or peep-show with scenes of London.” The sage Jigme Lingpa in his Discourses on India written in 1789, discusses the British, the Ottoman and the Moghul empires, and specifically describes England and its various manufactured exports: telescopes and modern weapons etc.. He describes in some detail contemporary novelties as a barrel-organ. But then he also mentions that “On top of this box “within a raised glass door the foreign countries are revealed, the images of these countries being laid down and made clear upon a mirror inside, and so by magical means the details of the great countries are beautifully drawn; and the design of the countries of the world which are executed upon various little panels appear enormous inside the glass door.” I am not certain if Jigme Lingpa was describing a zograscope, a peep-show or an optical viewing box of another kind.

John Claude White, the British resident in Sikkim, gave magic lantern shows in Bhutan, Sikkim and probably in the Chumbi area of Tibet in the early nineteen hundreds. The Victorian magic lantern was the precursor to the modern slide projector (and the PowerPoint computer program). The transparent photographic images, on glass slides, were projected onto a large cloth, which when wetted, enabled viewing by large audiences on both sides of the fabric screen. However the use of the magic lantern was not without its hazards. The type of fuel used by White to ignite the limelight that illuminated his slides, acetylene, produced a brilliant white light that was extremely hazardous. At one lantern show at Paro Dzong in Bhutan, an “accumulator” blew up scorching White’s face and badly singing his eyebrow, eyelashes and moustache.

British use of cinema in Tibet

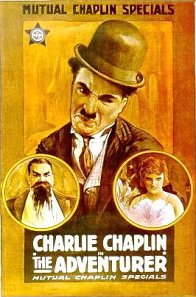

Following the Bell mission of 1920 subsequent British missions to Lhasa appear to have used cinema as “a little mild propaganda” and a means of creating a friendly and informal atmosphere in their dealings with the Tibetans. F.M Bailey showed films in Lhasa in 1924, one being a newsreel of the English king opening Parliament. In 1933 Frederick Williamson entertained the Thirteenth Dalai Lama with Charlie Chaplin. In her memoir Mrs. Williamson writes “In the popularity ratings Charlie Chaplin invariably had the edge on Fritz the cat. This was the same wherever we showed the films. In Lhasa, Charlie Chaplin was the great favourite; we had one of his films called The Adventurer, in which he played an escaped convict. The Tibetans renamed this film ‘Kuma’ (The Thief) and everyone wanted to see, including His Holiness, who laughed heartily throughout the performance.”

Following the Bell mission of 1920 subsequent British missions to Lhasa appear to have used cinema as “a little mild propaganda” and a means of creating a friendly and informal atmosphere in their dealings with the Tibetans. F.M Bailey showed films in Lhasa in 1924, one being a newsreel of the English king opening Parliament. In 1933 Frederick Williamson entertained the Thirteenth Dalai Lama with Charlie Chaplin. In her memoir Mrs. Williamson writes “In the popularity ratings Charlie Chaplin invariably had the edge on Fritz the cat. This was the same wherever we showed the films. In Lhasa, Charlie Chaplin was the great favourite; we had one of his films called The Adventurer, in which he played an escaped convict. The Tibetans renamed this film ‘Kuma’ (The Thief) and everyone wanted to see, including His Holiness, who laughed heartily throughout the performance.”

Dr. Pemba in his book Young Days in Tibet writes “The first motion picture I ever saw starred Charlie Chaplin. There were many reels with him as the hero, sometimes a criminal one, as in Easy Street. He had a terrific following in Dekyi Lingka (the British Mission), and people always yelled for the kuma (thief).”

Like the rest of the world, Tibetans (at least those with access to the cinema) were captivated by Charlie Chaplin. In much the way the French made him their own as “Charlot”, Tibetans hailed the little tramp as Charlie “Chumping”, or Charlie the Champion. The English word “champion”, with a slight change in the pronunciation, but used in the correct sense, had been incorporated into popular Tibetan lexicon since the twenties and thirties.

In the Williamson’s second visit to Lhasa they also showed newsreels of King George V’s Silver Jubilee Celebrations and of the Hendon Air Display, as well as other short films of educational value. Mrs Williamson mentions that when showing films in place like Paro in Bhutan her husband had a projector that worked with batteries that could only be charged in Lhasa, and she goes on to describe the electricity system in Lhasa. “The current was conducted over a distance of about four miles by high-tension cable from the power house beyond Trapchi to a sub-station in the city situated just below Ringang’s own house.” Ringang being the engineer who built the power plant. She also mentions that Ringang’s brother had a private-theater in his house. I have not heard anything to confirm this, but it does appear that interest in the cinema was growing in Lhasa.

For instance, Spencer Chapman mentions that Tsarong received the following letter in 1936 from his son who was in school in Darjeeling: “Is there any talking picture in Lhasa? I heard there is talking picture in Lhasa, and every gentlemen doesn’t work, but go to see picture every night. I have nothing more to say.”

The Gould Mission of 1936 not only brought with them a number of early Charlie Chaplin one-reelers but also Rin-Tin-Tin in The Night Cry (1926), which became a big hit in Lhasa. I heard from an old aristocrat who had attended Frank Ludlow’s school at Gyangtse, that he had seen Lassie Come Home, at Dekyi Linga, and that it was very popular with Tibetans. According to Gould, newsreels of military parades and royal pageants seem to have gone down well with the local audience and “…it gives the right impression of British power and purpose.” Later during the war such Pathé news reviews as Victory in the Desert, became big favourites.

The Gould Mission of 1936 not only brought with them a number of early Charlie Chaplin one-reelers but also Rin-Tin-Tin in The Night Cry (1926), which became a big hit in Lhasa. I heard from an old aristocrat who had attended Frank Ludlow’s school at Gyangtse, that he had seen Lassie Come Home, at Dekyi Linga, and that it was very popular with Tibetans. According to Gould, newsreels of military parades and royal pageants seem to have gone down well with the local audience and “…it gives the right impression of British power and purpose.” Later during the war such Pathé news reviews as Victory in the Desert, became big favourites.

One Tibetan informant, who attended a film show at a Dekyi Linga Christmas Party as a child, described his experience to me. He had never seen a movie before and had no idea of what to expect, but was looking forward to it, nonetheless. He initially thought that one of the long shiny Christmas decorations that hung from the ceiling and twisted and turned, was the cinema. He stared at it till an older person told him gently “Ganden-la, what are you staring at? Look there; that is the “beskop”. He vaguely recalled a confusing scene of old cars chasing each other. A silent film, perhaps a Mack Sennet comedy.

One Tibetan informant, who attended a film show at a Dekyi Linga Christmas Party as a child, described his experience to me. He had never seen a movie before and had no idea of what to expect, but was looking forward to it, nonetheless. He initially thought that one of the long shiny Christmas decorations that hung from the ceiling and twisted and turned, was the cinema. He stared at it till an older person told him gently “Ganden-la, what are you staring at? Look there; that is the “beskop”. He vaguely recalled a confusing scene of old cars chasing each other. A silent film, perhaps a Mack Sennet comedy.

Tibetans first called the cinema beskop, from “bioscope” one of the early terms for movies (as kinema, vitascope, etc.) and now apparently used only by South Africans, Nepalese and Tibetans. These days Tibetans (both in Tibet and in exile) use the term lok-nyen, a direct translation of the Chinese dian-ying (electric shadow).

The movie shows at the British Mission were very popular and nearly every account by mission personnel mentions uninvited but enthusiastic monks trying to push their way in. Basil Gould was clear about what the Tibetan clergy thought of the cinema. “Monks were amongst the most ardent of our cinema clientele. There is nothing which Tibetans like better than to see themselves and their acquaintances in a frame or on the screen.”

From its inception in Tibet, the cinema does not seem to have been regarded as anything magical or taboo, but merely excellent entertainment. In one case its educational value appears to have been noted. Gould wrote that “A senior monk official recently suggested that it would cause much satisfaction in Lhasa if arrangements could be made to take a cinema record of holy places in Burma, India and Ceylon and to shown in Lhasa.”

The Chinese academic Ma Lihua in her book Old Lhasa, writes of Tibetan superstitions about photography, and mentions that Tibetans feared that the camera “captured the soul”. According to Harrer and Kingdon-Ward, far from being afraid, curious Tibetan bystanders could be quite a nuisance, peering into the lens from the other side of the camera, or a theodolite in Harrer’s case.

Robert Ford who lived for some years in Tibet and worked for the Lhasa government as a radio operator, expresses a wariness of condescending faux-ethnological observations by European travelers of native credulity and superstition. In his book Captured in Tibet, he writes, “I arranged for her (the district governor’s wife) to speak by radio to her parents in Lhasa, and she was grateful but too preoccupied to be impressed by my little conjuring tricks although she had never seen a radio before. I had the same experience throughout the journey. People were intrigued, and looked for the man in the box, but I was never credited with any magical powers. This made me skeptical about those travelers’ tales of Europeans who were acclaimed as white magicians or even gods when they demonstrated a few scientific toys to remote peoples with religions of their own.”

Tibetans just used the loanword “beskop” for the cinema, as I mentioned earlier, and there is no other descriptive term for it hinting at anything supernatural or magical. Incidentally, the early Chinese term for movies was shen-ying (magic shadow), or “Shadow Magic” as the Chinese director Ann Hu has titled her interesting feature film (of 2000) that depicts the introduction of the movies to China at the beginning of the 20th Century.

Monks and other ultra-conservative elements in Tibet may have bitterly resisted the creation of a modern military force, the English schools at Gyangtse and Lhasa, and football (soccer) matches, but somehow they never got around to opposing the cinema. Instead, they shoved their way into movie shows, as they were doing at video-parlours in McLeod Ganj in the nineties. No clerical objection or outcry was raised at the opening of a commercial cinema hall in the holy city. In fact the last cinema hall built before ‘59 was co-owned by a monk official.

Commercial cinema in Tibet

The first commercial cinema hall in Lhasa was established by two Ladakhi Muslims, the Radhus, whom the Tibetans called the “Tsakhur” brothers, after the name of their house in the city. Muhammad Ashgar and Sirajuddin got their start in the movie business by projecting picture slides on a cloth screen using a bicycle “magneto” which they worked by pedalling. According to Abdul Wahid, who had married the Radhu’s daughter “The profits from this allowed them to import a real cinema projector from India which they proposed to use in Lhasa.” Official permission to open the cinema came from the high official, Kuchar Kunphel-la, for whom the Radhu brothers first arranged a special film show. If we accept Wahid’s account, then the first cinema hall in Lhasa was established before 1934 – prior to Kunphel-la’s fall from power. But this is not certain. Their oldest Radhu brother Khwaja Abdul Aziz regarded the enterprise with unease as he was not too certain whether the profits earned from exhibiting animated images were legal from the point of Islamic law. But in his in his memoir, Tibetan Caravans, Abdul Wahid writes that the cinema “would bring them considerable revenue”.

One informant told me that the cinema was located near Shatra mansion, in an old converted residential building, just south of the Jokhang near the Lingkor. Another informant agreed about it being south of the Jokhang and near the Lingkor, but insisted that it was closer to the house of Bumthang Drunyig Chenmo and not the Shatra mansion. This informant told me that the hall seated about a hundred people, perhaps less. There was a balcony section which seated twenty to thirty people, but my informant had never been up on it as each seat there cost twenty srang. It was cheaper downstairs in the stalls.

The balcony section had a useful facility in the way of a Muslim translator who narrated the story of the film to the Tibetan audience. One might perhaps see in this a reflection of the tradition of benshi narrators in the days of silent films in Japan. Kurosawa’s older brother was such an artist. The young Muslim was a city lad with a free and easy way about him, and on one occasion, when describing a love scene, he seemed to have overstepped the boundary of decent speech. Tibetans are generally open to racy talk, but can get quite prim and prudish when relatives and parents are around. Someone got up and slapped the young narrator hard on the face.

This was the theater where the famous Anarkali, the great Moghul romance, was screened. The tragic story of a beautiful slave girl buried alive as punishment for her love of the prince Salim (son of the Emperor Akbar), this film holds a place in the hearts of many older citizens of Lhasa, the same way as Gone with the Wind might with some older Americans. When the same title played too long in Lhasa and audience numbers dropped, the Radhus would move their projector to Shigatse, and hold outdoor shows there. One informant remembered such an outdoor screening and hearing the rumble of the generator outside.

This was the theater where the famous Anarkali, the great Moghul romance, was screened. The tragic story of a beautiful slave girl buried alive as punishment for her love of the prince Salim (son of the Emperor Akbar), this film holds a place in the hearts of many older citizens of Lhasa, the same way as Gone with the Wind might with some older Americans. When the same title played too long in Lhasa and audience numbers dropped, the Radhus would move their projector to Shigatse, and hold outdoor shows there. One informant remembered such an outdoor screening and hearing the rumble of the generator outside.

The late Ngawang Dhakpa la from the Chithiling neighbourhood of Lhasa, told me that he saw Tarzan and Jungle Jim films in this theater. He recalled one Jungle Jim film, where about half the side of the projected image was blurred. It appears that when the films were being transported across the Kyichu by coracle, the boat capsized and some film containers fell into the river. Though they were recovered the films were partially damaged. Lowell Thomas Jr. also mentions that Tarzan and Marx Brothers films were popular in Lhasa.

Alo Chonze, the pioneer political activist and controversial entrepreneur, launched a venture to build a cinema hall complex in the Songra locality, immediately north-east of the Jokhang, sometime in the mid-fifties. Chonze had big ideas and intended to put up a modern building, dispensing with the many pillars required in traditional Tibetan constructions. He planned to import steel girders from India and have a big open auditorium with no obstructions to the audience’s view of the screen. He also planned to construct rows of shop-fronts along the outside length of the building, for rent or sale. But somehow the whole project fell through. I was told he managed to get some investors, but perhaps there were not enough of them, or this all happened around the time when he was arrested for being one of the leaders of the underground “Mimang” organization that put up posters around the city denouncing the Chinese occupation force.

Alo Chonze, the pioneer political activist and controversial entrepreneur, launched a venture to build a cinema hall complex in the Songra locality, immediately north-east of the Jokhang, sometime in the mid-fifties. Chonze had big ideas and intended to put up a modern building, dispensing with the many pillars required in traditional Tibetan constructions. He planned to import steel girders from India and have a big open auditorium with no obstructions to the audience’s view of the screen. He also planned to construct rows of shop-fronts along the outside length of the building, for rent or sale. But somehow the whole project fell through. I was told he managed to get some investors, but perhaps there were not enough of them, or this all happened around the time when he was arrested for being one of the leaders of the underground “Mimang” organization that put up posters around the city denouncing the Chinese occupation force.

The Diki Wolnang or the Happy Light movie theatre was built in 1958, and was the joint venture of the monk official Liushar Thupten Tharpa and the Muslim businessman Ramzan. The building was a concrete and steel structure and could hold a thousand people, according to the journalist Noel Barber. It was located west of the Jokhang towards the Yuthog bridge. To alert the Lhasa public to their shows the cinema management would play 78rpm records of Hindi songs over loudspeakers, about a hour before each screening and could be heard for a considerable distance throughout the city. This annoying practice carried over into exile where the Tibetan Drama Party (now TIPA) would aim blaring loudspeakers at the town of McLeod Ganj. During the ’59 Uprising, the Happy Light cinema was held by Chinese troops. According to Noel Barber who wrote a book on the conflict (From the Land of Lost Content) Tibetan forces defending the Jokhang bombarded the cinema hall with mortar fire, and then stormed it. One group of Tibetan fighters made their way to the back of the building and climbed up into the projection-room. Then coming out on the balcony they fired down into the main hall where many Chinese soldiers were sleeping.

Lhasa was not the only city where Tibetans saw their first movies. In the 40s and 50s the Novelty Bioscope Hall in Kalimpong, a corrugated tin structure below the football (or mela) ground, provided entertainment not only to the citizens of the town, but also to visitors from Tibet. Since many of these were rough-tough muleteers and caravan personnel, looking to unwind after their long and dangerous journey across the Tibetan highlands, the Novelty Theater employed Tibetan ushers who were as adept with knives as with their flashlights.

For many Khampas, the Chinese owned movie hall at Dhartsedo was probably their first introduction to the cinema. We unfortunately have little information about this institution, other than that the local Christian missionaries disapproved of it as a corrupting influence on the native population, especially the “unsophisticated” Tibetans. One Khampa told me he saw an inji beskop about an endearing (sha-tsamo) little girl. Shirley Temple films were popular in China during Guomindang times. With the arrival of the Red Army at the end of 1949, the cinema was shut down, and the hall used for political meetings and denunciation rallies. The cinema hall owner probably committed suicide by jumping into the foaming Dharchu river, as did so many other members of the city’s business community, Tibetan and Chinese.

Chinese propaganda films screening

The Chinese occupation force in Lhasa initially screened their propaganda films in the evenings, at the horse-market square of Wontoe Shinga. A large white cotton screen was hung on the back wall of the Trimon house on the east side of the square. My informant told me that some of the houses around the square had step-like raised abutments, where you could sit, if you got there early enough. It could get quite cold in the square in winter, and my informant remembers him and his friends inviting girls in the audience to sit on their laps.

The films screened were the usual documentaries and newsreels about tractor plants, dams, farming communes, factory openings, the Korean War, and the life of Joseph Stalin (after his death). The one feature film that all Tibetans seemed to have genuinely enjoyed was Bai Mao Nu (1950) or The White Haired Girl, directed by Wang Bin & Shui Hua. The film tells the story of a courageous peasant girl who hides from a despotic landlord and his henchmen in the mountain wilderness of Hebei, where her hair becomes white from her trials. She is eventually saved by her sweetheart, a Communist soldier in the Eighth Route Army fighting the Japanese. The film was remade as a revolutionary ballet during the Cultural Revolution, under the “artistic” guidance of Madam Mao.

The films screened were the usual documentaries and newsreels about tractor plants, dams, farming communes, factory openings, the Korean War, and the life of Joseph Stalin (after his death). The one feature film that all Tibetans seemed to have genuinely enjoyed was Bai Mao Nu (1950) or The White Haired Girl, directed by Wang Bin & Shui Hua. The film tells the story of a courageous peasant girl who hides from a despotic landlord and his henchmen in the mountain wilderness of Hebei, where her hair becomes white from her trials. She is eventually saved by her sweetheart, a Communist soldier in the Eighth Route Army fighting the Japanese. The film was remade as a revolutionary ballet during the Cultural Revolution, under the “artistic” guidance of Madam Mao.

The Chinese also screened Indian films produced and directed by Indian Communist and Socialist filmmakers. One was Bimal Roy’s award winning (the Prix Internationale at Cannes) portrayal of the suffering of the Indian peasantry, Do Bhiga Zamin (Two Acres of Land). Another very popular Bombay film in Tibet (and also in China and the Soviet Union) was Raj Kapoor’s Awaara (The Tramp or the Wanderer). The story of petty criminal, corrupted by society, but redeemed by the love of Rita, his childhood friend. The Chinese language version, Liu Lang Zhe, even had the song “Awara Hun” I am a wanderer, adapted and sung in Chinese.

The Chinese also screened Indian films produced and directed by Indian Communist and Socialist filmmakers. One was Bimal Roy’s award winning (the Prix Internationale at Cannes) portrayal of the suffering of the Indian peasantry, Do Bhiga Zamin (Two Acres of Land). Another very popular Bombay film in Tibet (and also in China and the Soviet Union) was Raj Kapoor’s Awaara (The Tramp or the Wanderer). The story of petty criminal, corrupted by society, but redeemed by the love of Rita, his childhood friend. The Chinese language version, Liu Lang Zhe, even had the song “Awara Hun” I am a wanderer, adapted and sung in Chinese.

By the mid-fifties the Chinese had built indoor auditoriums at the Chinese Military Headquarters, and the Tibet Autonomous Region complex, where they showed movies and staged cultural performances. From the mid-fifties the occupation authorities issued a ruling that all films imported into Tibet had to be censored. Perhaps this development contributed to the decision of the Radhu family to close their cinema hall and leave Lhasa for good.

By the mid-fifties the Chinese had built indoor auditoriums at the Chinese Military Headquarters, and the Tibet Autonomous Region complex, where they showed movies and staged cultural performances. From the mid-fifties the occupation authorities issued a ruling that all films imported into Tibet had to be censored. Perhaps this development contributed to the decision of the Radhu family to close their cinema hall and leave Lhasa for good.

NOTE:

Besides the textual sources, most of the information for this piece came from conversations I had (over the years) with the late Nornang Ganden la, Lingtsang Thupten Tsering la, the late Chitiling Ngawang Dhakpa la, the late Gyen Lutsa la, Gyen Norbu Tsering la, Tashi Tsering la (of AMI), Tsering Wangchuk la, Jamyang Dorjee la, my uncle TC Tethong, my late grand uncle Tesur Palden Gyaltsen, my late mother, and many other friends and relatives. I must also thank Sonam Dhargyal la for sending me CD copies of films from Tibet.

happy-light-bioscope-theatre-other-stories-part-ii-jamyang-norbu

Festival of Tibetan Films and Films about Tibet FLIM Prague

Festival of Tibetan Films and Films about Tibet FLIM Prague